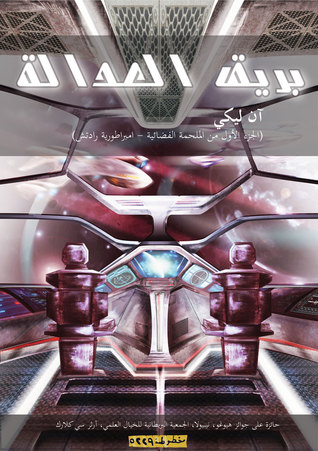

Very little people know this about me – because I haven’t shouted off rooftops about it – but last year, I completed my very first translation of a novel, from English into Arabic. Not only was I new to translating fiction, but the book that I translated was also the triple-award-winning science fiction novel, Ancillary Justice. It was the first in a trilogy written by Ann Leckie, and it was also her debut novel.

The fact that it won all three major science fiction awards – the Hugo, the Nebula, and the BSFA awards – put immense pressure on me to perform my very best, and I managed to pull it off. How I came to actually translate the novel was a story in itself, but that’s for another day. Today, I just want to muse upon how one goes about translating a genre such as science fiction, from English into Arabic.

I suspect many of the readers of this blog do not understand Arabic, merely for the fact that it’s written in English, so I’m going to preface my thoughts with some facts about Arabic itself, as a language.

Arabic is a very rich, poetic language. You can have one word with meanings that range from the superficial level to the very deep level. You can have concepts that have different names, with each one of them having a range of meanings that showcase the concept in varying degrees of intensity. It’s kind of like when you say something is blue, you’re just touching on the general color, but if you say sky blue, navy blue, or denim blue, you’re portraying the different levels of bluish-ness; except most of the time you’re using the same word, not changing words around or adding words.

Arabic is a language in which context is extremely important, and a simple change of the tense can be the difference between “tired” and “suffering from fatigue”. Arabic is also a language where modern concepts, especially ones related to technology, are usually expressed using words that are re-purposed to mean different things today than what they meant a couple of centuries ago.

It can be confusing sometimes, because there are Arabs who prefer to use borrowed words rather than using Arabic words that mean the same thing. For example, in some parts of the Arab world, cellphones (or mobile phones) are named “mobile”, while in other parts of the Arab world they’re named “jawwal” … the first one is obviously a borrowed word, and the second one is an Arabic word that has been re-purposed, and it actually means “something that wanders (or moves) around quite a lot”.

What does all of this have to do with science fiction?

Here’s the deal: in science fiction writers are creating worlds of their own, in which words don’t necessarily mean the same thing as we are familiar with in the real world. And that’s where things can get lost in translation, in a very serious manner.

In order to translate a piece of fiction accurately, you have to be able to put yourself inside the author’s head, and start thinking in a way very similar to the original author. This, as you can imagine, is quite hard with regular fiction that is talking about the real world, let alone science fiction that is talking about completely different worlds with concepts that were dreamed up by an author.

You have to immerse yourself in the author’s constructed world until it becomes as familiar as the real world. You have to be able to imagine the spaceships shooting across the vacuum of space, and the androids talking, walking, and eating like humans.

Then you start facing the terminology issues: what are you going to call FTL in the target language without making it sound too clunky? How are you going to explain collective consciousness?

Given that scientific discourse is rarely conducted in Arabic at the levels required to tackle these topics, it is quite understandable that few people have set about to translate science fiction into Arabic. It requires a high level of creative translation, and making sure that you stay faithful to the meaning rather than the words themselves.

My Experience

I must admit, when I was first approached by the publisher, I almost turned the project down because I didn’t think I was up for it. I always wanted to work on translating books, but I never expected to start that early in my career, and I certainly didn’t expect to translate science fiction right from the get-go.

Nevertheless, I submitted a sample translation, and she loved it. There was some feedback related to my writing style – I’d never written for publishing in Arabic before – but those I fixed quite easily. I was worried most about allowing myself to get creative with the translation, and my choice of words for the science fiction concepts in the novel, but I was assured that it was great.

It was first and foremost, an exercise in self-confidence. I was going through a tough time personally as well, but I managed to pull it off. The publisher acted as an editor as well, and I was quite pleased when I noticed that she hadn’t made any changes to many of the words I used to explain the science fiction concepts encountered in the novel.

My favorite part of the project was finding ways to translate the concepts of collective consciousness and “one brain, many bodies” that are portrayed in Ancillary Justice. It is a story about an “ancillary”, a human being that was turned into part of a ship, stripping him/her of individuality, who finds herself/himself stranded from the ship years after it was blown up by a traitorous clone of the leader of the Radch Empire.

Another interesting concept was the ambiguity of gender in the Radch culture. Arabic is well-known for it’s gendered nouns, not just nouns that describe people, such as “waitress” and “hostess”, but everything from “sun” to “computer” has a gender. Nouns can also switch genders depending on whether they’re single or plural, such as “moon”, which is masculine when singular, but feminine when pluralized. It was probably the second-most challenging part of this translation, and my second-most favorite. The publisher later on decided to add a note to the readers explaining the ambiguity in gender, due to the novelty of the idea for Arab readers.

Overall, the experience was quite fascinating, and I cannot wait for the next opportunity to tackle a challenging book translation!

Do you have any similar experiences in your line of work? What is the next challenge that you cannot wait to tackle?

Hey Bouchra!

Great post and congratulations on the translating a book like that! You’re amazing my friend. To answer your question the next project that I actually am working on is a fundraiser. 🙂 I hope to be as successful with it as you were with translating this book. Any pointers? 🙂 Wonderful post.

Namaste

Angela

Hey Angela! Thank you for your comment 🙂

Hmmm. I have no experience with fundraisers, but if you’re doing it online, then I might be able to offer you some advice! When marketing your fundraiser, make sure to showcase the benefits of someone contributing, and why it’s important for them to care. Always make it about what it will be for them, then make it about what it will be for the people benefiting from the funds raised 🙂

Another tip I was reading recently was about an experiment someone ran on fundraisers, and they noticed that when they showed a video of a group of people suffering from a famine in an African country, the number of people donating was less than when they showed a video with the story of one person who was suffering from the same famine. People relate to individuals and individual stories more; I believe that is the reason someone like Malala Yousafzai has gotten a lot of attention compared to all the other girls suffering from similar predicaments, across the globe.

So, in a nutshell, show them the benefits, and personalize the story 🙂

Good luck! Keep me posted on your progress!

Cheers,

Bouchra

What a fascinating insight into both the Arabic language and also the process and your skills as a translator Bouchra! A great reminder to me, too of the advantages of pushing outside of that comfort zone 🙂

Bouchra, I found your post FASCINATING!! The complexity of your task with the added pressure of doing it for a highly-acclaimed book must have been incredibly daunting. But you pushed through your fears and worries and accomplished an incredible feat!! Congratulations on such an accomplishment. Thank you for sharing your story – it truly was wonderful to read!!